Communities under siege

Untold toll of military bombardment in the Philippines

Throughout the country, the Philippine government has been conducting a devastating, all-out war against the armed insurgency. But civilian communities -- and the environment -- have been bearing the brunt of the attacks. Altermidya has documented and verified at least 173 cases of aerial bombardment, artillery fire, and strafing since President Rodrigo Duterte took office in 2016 until today under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. (This documentation did not include the sustained aerial bombardment of the city of Marawi against purported ISIS-inspired terrorists in May-October 2017.) The war has so far displaced over 17,000 families in provinces across the country. Disturbingly, our findings show that only 17.4 percent of these military strikes hit actual rebel positions. The vast majority, it turns out, devastated communities of farmers, fisherfolk, workers, and indigenous peoples.

Mario Empon, in a press conference on the fact-finding mission on the incidents in Brgy. Caputo-an, Las Navas, Northern Samar in November 2019. (Contributed Photo)

Mario Empon, in a press conference on the fact-finding mission on the incidents in Brgy. Caputo-an, Las Navas, Northern Samar in November 2019. (Contributed Photo)

In a public gathering in 2020, Carlos Baluyot narrates the issues confronting farmers in Las Navas. The previous year, their crops were devastated by pests, destroying entire harvests. On top of these, their community in Barangay Capoto-an was subjected to a series of aerial bombardment and strafing. (Aninaw Productions)

In a public gathering in 2020, Carlos Baluyot narrates the issues confronting farmers in Las Navas. The previous year, their crops were devastated by pests, destroying entire harvests. On top of these, their community in Barangay Capoto-an was subjected to a series of aerial bombardment and strafing. (Aninaw Productions)

The bombing of Capoto-an

At five in the morning on October 26, 2019, Jenalyn Diaz was asleep, her children Joshua, 5, and Joan, 3, curled up beside her in their humble nipa hut in Barangay Capoto-an, Las Navas, Northern Samar. The quiet of dawn was shattered by a thunderous explosion that ripped through the air, jolting the family out of their slumber and nearly tossing them out of bed.

“We scattered in panic, running in different directions inside the house,” Jenalyn recalled. The explosion, she estimated, had come from just 10 meters away.

Before the shock had even settled, two more explosions followed, deafening and powerful. As the dust settled and their ears rang from the blasts, the small family suddenly found themselves face-to-face with armed soldiers—members of Task Force Storm of the 8th Infantry Division of the Philippine Army.

The soldiers, guns raised, barked orders for them to leave the house. Jenalyn and her children, terrified, obeyed. But as they watched in helpless confusion, the soldiers began to ransack their modest home—ripping through their clothes, overturning their kitchen, scattering their meager belongings. Outside, neighbors witnessed the soldiers seizing chickens and goats from nearby farms. The ground was littered with rice, the precious grains they had painstakingly harvested, now reduced to waste.

Mario Empon, a farmer and resident of Capoto-an, stood in disbelief at what had been left behind. “Where plants used to grow, there was now this massive crater in the ground,” he said, describing a hole seven meters deep. The gaping scar on the land lay nearly a kilometer from the village center, visible even in 2021 satellite images on Google Earth—about 10 meters across, a grim reminder of the devastation.

Just hours after the airstrikes, the 8th Infantry Division released a statement, hailing the destruction of what they claimed was a rebel camp of the New People’s Army (NPA). According to Captain Reynaldo Aragones Jr., the camp had been home to 50 armed insurgents led by a man named Ceriaco Jerusalem. “The Joint Task Force Storm, under the AFP and the Philippine Army, coordinated the operation to locate and destroy this group, which had been extorting from the local communities,” Aragones said.

But over the following days, the villagers of Capoto-an challenged the military’s narrative. They described months of military encirclement, with soldiers restricting their movements. Empon recalled how, in August of that year, the villagers were rounded up and forced to gather in the local "dancing hall." There, under the watchful eyes of soldiers led by 1st Lt. Daniel Sumawang, a supposed "former rebel" informer accused six of them of being NPA members.

This is not an isolated incident. For decades, counter-insurgency operations in the Philippines have been marred by stories of violence and displacement, but under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, aerial assaults intensified. Bombings, artillery shelling, and strafing became common tactics in “pursuit operations” against rebel forces.

Altermidya has documented at least 173 instances of aerial bombardment, artillery fire, and strafing since Duterte took office, displacing over 17,000 families in provinces across the country and taking the lives of at least 10 civilians. Disturbingly, our findings show that only a fraction these military strikes hit actual rebel positions. The vast majority, it turns out, devastated civilian communities—farmers, fisherfolk, workers, and indigenous peoples, left to pick up the pieces after the military moved on.

Crater created by the explosion was, according to Mario Empon, at least seven meters deep. It destroyed at least three houses in its vicinity.

One of the three houses destroyed in the bombing.

Residents took photos of shrapnels from the blast.

Google Earth satellite image of one of the possible bomb craters caused by the October 26, 2019 bombing, around 500 meters from the barangay proper.

For days in March 2023, indigenous people of Barangay Gawaan in Balbalan, Kalinga were terrorized by a series of bombings, purportedly in pursuit of rebels.

Terror in Gawaan

In the early hours of March 5, 2023, the village of Barangay Gawaan in Balbalan, Kalinga was jolted awake by explosions. The night sky lit up with flashes as bombs fell on the mountains surrounding the community.

Eufemia "Kam-ay" Bog-as, a young indigenous organizer from the Salegseg tribe, was among those who witnessed the terrifying scene unfold. “We woke up to the sound of explosions,” Kam-ay recalled. “It felt like the earth was breaking apart. The house was shaking like it would collapse.” She and her family rushed outside, unsure of what was happening.

As they stood under the dim, misty sky, they spotted something in the air, its cold light visible through the clouds. “We saw what looked like a drone, and then the bombs started dropping near the mountains,” she said. The mountains, with its forested pasture lands where farmers kept their livestock, became the apparent target of military airstrikes that shook the entire village. “In those mountains, farmers had their carabaos. They placed their carabaos there so they don’t have to tend to them every day.”

Six blasts in total tore through the area, leaving residents terrified. Just hours before, they celebrated the last night of the Manchatchatong Festival, a peaceful and joyous occasion for the people of Balbalan.

“It was confusing. We had visitors during our fiesta, and everything was calm,” Kam-ay wondered.

In the aftermath, fear and uncertainty gripped the community. When the police arrived later that morning, they claimed the military had targeted the area due to "sightings" of armed rebels. But for many, including Kam-ay, the explanation felt hollow. “The Barangay Captain didn’t know anything, and then the police said it was because of rebels. But we live here—we know this land. There were no rebels that day.”

The fear intensified when, at around 7 a.m., two farmers who had gone to check on their carabaos were detained by soldiers stationed in Sitio Uta. The men, who simply intended to tend to their livestock, were held without explanation. When other members of the barangay council and the men’s families arrived to intervene, they too were detained, bringing the number of detained individuals to nine. The farmers were released only in the afternoon after tensions began to rise.

Reports surfaced the next day, March 6, about military positioning their artillery, including cannons and howitzers, in the barangay, aimed at Gawaan.

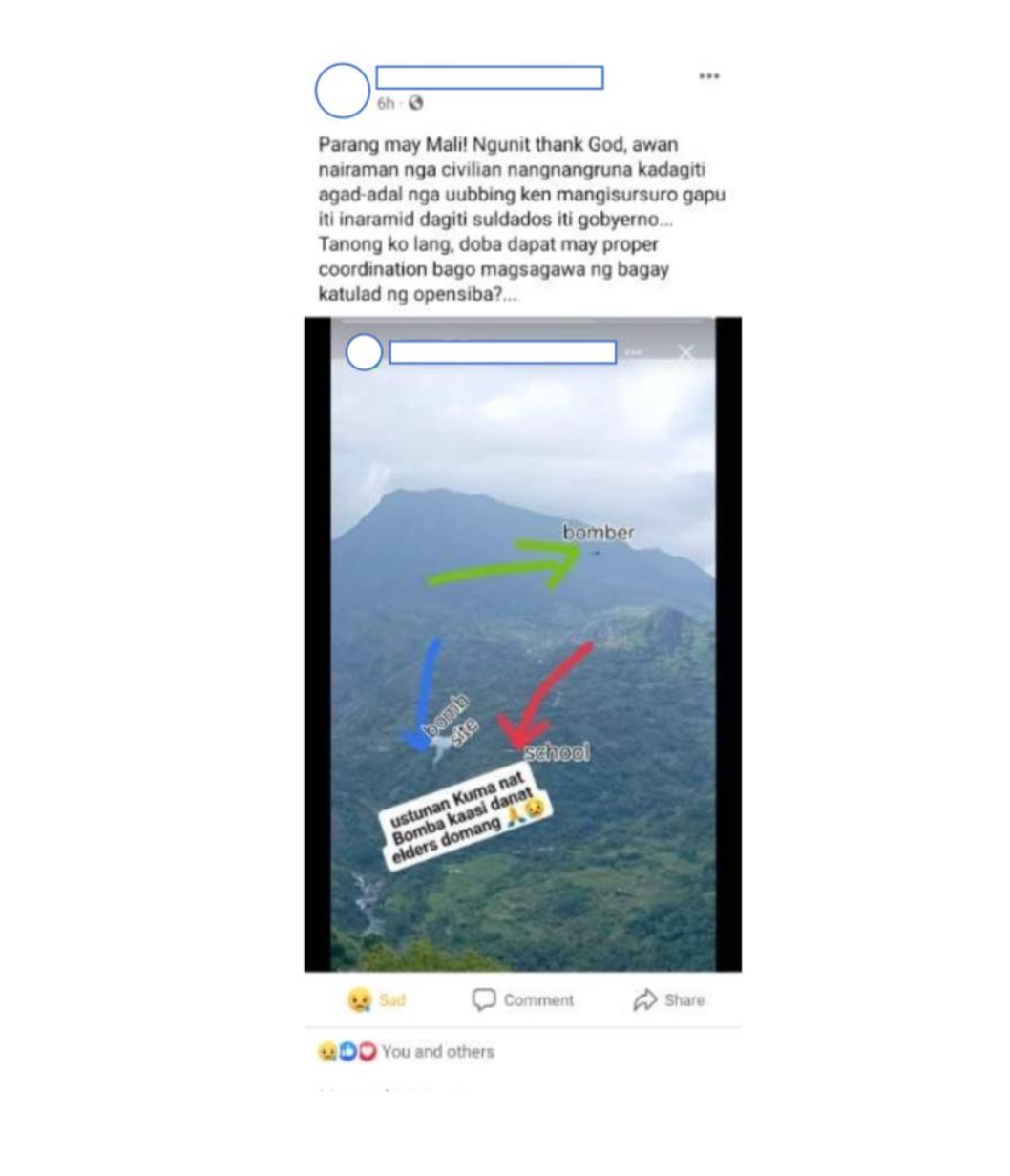

Three days later, on March 9, military helicopters returned, this time dropping bombs near a local school, where 60 to 65 students were attending class. The school, normally a place of safety and learning, became a terrifying scene as residents estimated that six to nine bombs fell dangerously close to the students.

Eufemia Bog-as recounts her community's experience with the aerial bombardment in Barangay Gawaan in Balbalan, Kalinga on March 5, 2023. (Altermidya)

Eufemia Bog-as recounts her community's experience with the aerial bombardment in Barangay Gawaan in Balbalan, Kalinga on March 5, 2023. (Altermidya)

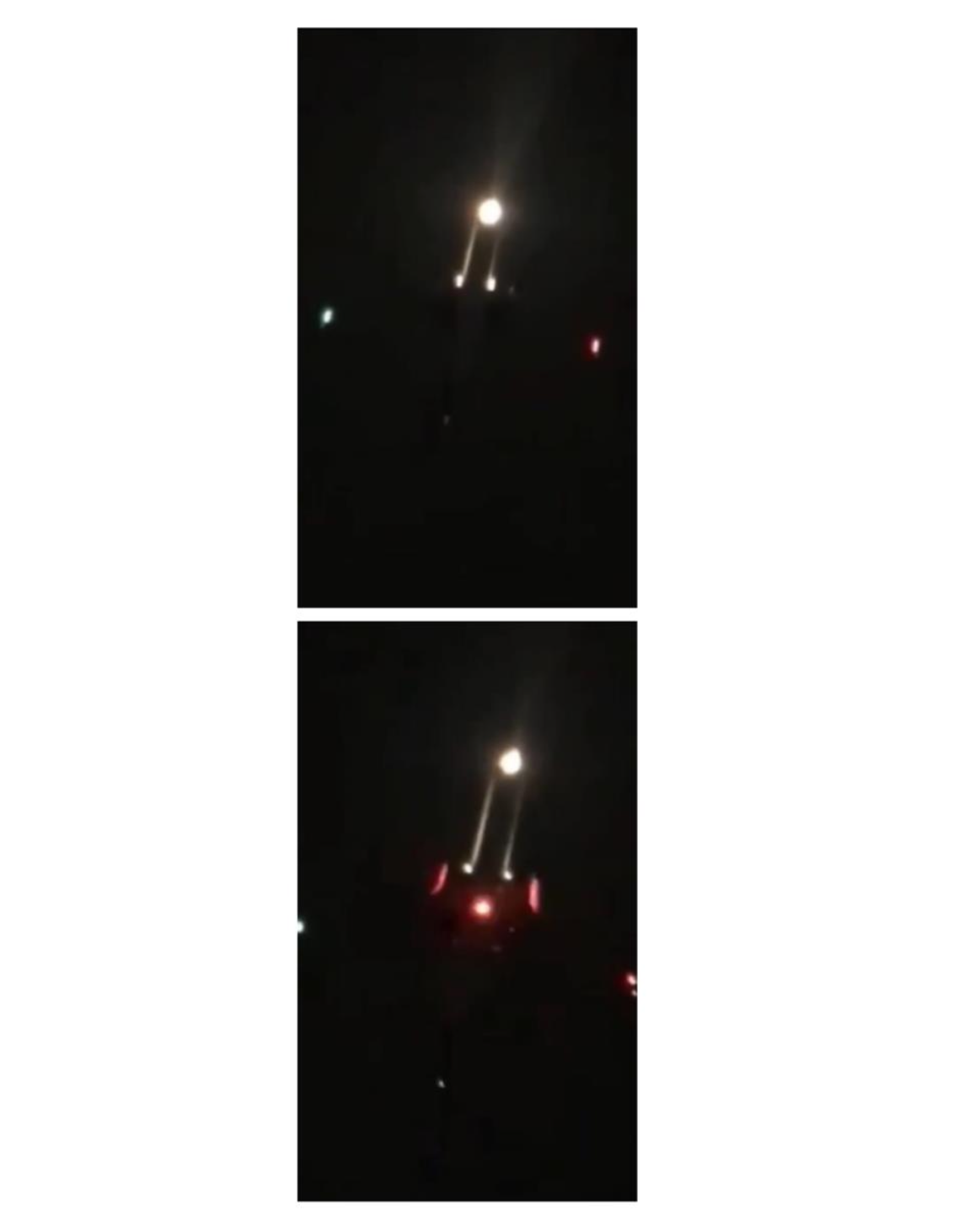

Screenshots of what appeared to be fighter jets, from a video taken by a resident at 2 A.M. of March 5, 2023. (Image courtesy of Eufemia Bog-as)

Screenshots of what appeared to be fighter jets, from a video taken by a resident at 2 A.M. of March 5, 2023. (Image courtesy of Eufemia Bog-as)

A Facebook post of a Gawaan resident shows how near the bombing site was to the elementary school. It had the caption (translated in English): "This seems to be wrong! But thank God, there were no civilians hurt especially the students and teachers because of what the government soldiers did..." (Image courtesy of Eufemia Bog-as)

A Facebook post of a Gawaan resident shows how near the bombing site was to the elementary school. It had the caption (translated in English): "This seems to be wrong! But thank God, there were no civilians hurt especially the students and teachers because of what the government soldiers did..." (Image courtesy of Eufemia Bog-as)

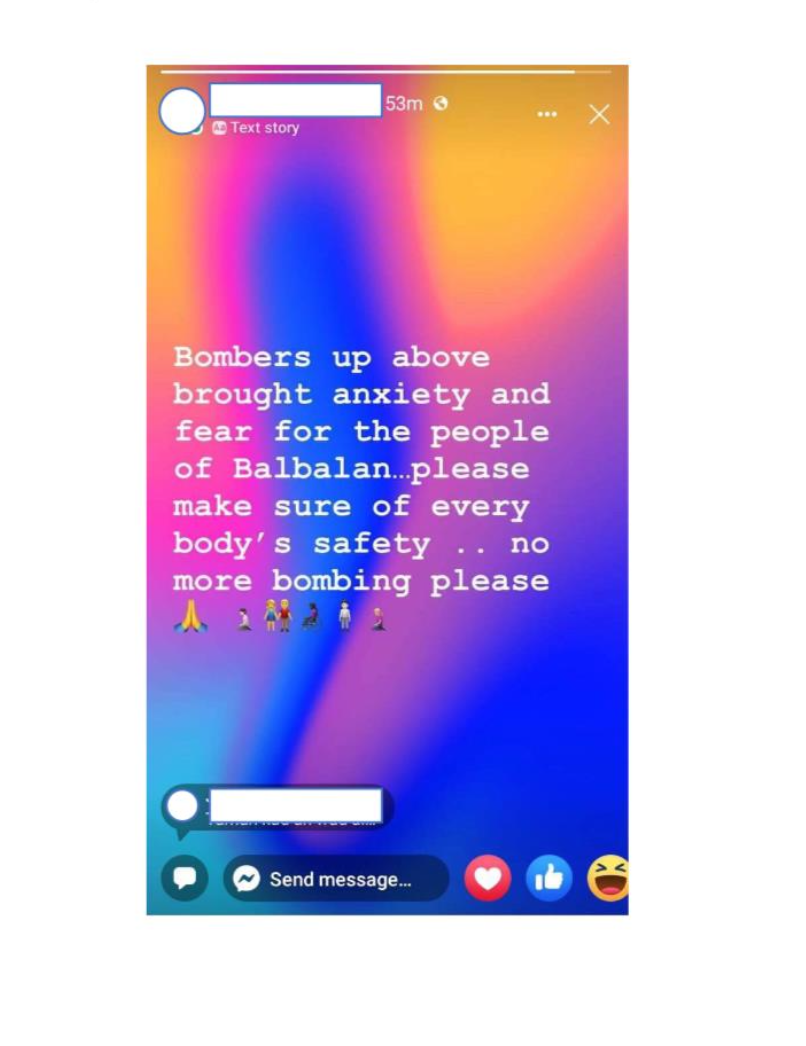

Facebook post of a concerned citizen from Gawaan.

Facebook post of a concerned citizen from Gawaan.

A Facebook story of a concerned citizen of a photo of a howitzer apparently placed at Barangay Guisang poblacion, which is facing Gawaan. (Image courtesy of Eufemia Bog-as)

A Facebook story of a concerned citizen of a photo of a howitzer apparently placed at Barangay Guisang poblacion, which is facing Gawaan. (Image courtesy of Eufemia Bog-as)

Photo by a Gawaan resident of some of the soldiers that held the farmers for seven hours on March 5, 2023. (Image courtesy of Eufemia Bog-as)

Photo by a Gawaan resident of some of the soldiers that held the farmers for seven hours on March 5, 2023. (Image courtesy of Eufemia Bog-as)

Interactive map of aerial bombardment, artillery shelling and strafing from 2016 to 2023. From data gathered by Altermidya. Scroll through the map and click on a pin to see details (some with videos/photos) of each incident.

Altermidya report on the air strikes against indigenous communities in the Cordillera region in 2023.

Bukidnon experienced the most number of military attacks with 27, followed by Northern Samar with 19 and Davao del Norte with 11.

White phosphorus was used before the actual bombing in Malibcong, Abra on April 7, 2017. According to the military, its purpose was to demarcate the area to be bombed. But according to the World Health Organization: "White phosphorus is harmful to humans by all routes of exposure. It can be absorbed in toxic amounts following ingestion or dermal/mucosal exposure. The smoke from burning phosphorus is harmful to the eyes and respiratory tract as phosphorus oxides dissolve in moisture to form phosphoric acids. Systemic effects may be delayed for up to 24 hours after exposure. In severe cases of exposure, delayed systemic effects can include cardiovascular effects and collapse, as well as renal and hepatic damage and depressed consciousness and coma. Death may occur from shock, hepatic or renal failure, central nervous system or myocardial damage."

'War in the skies' of Negros

Felipe Gelle, a human rights worker from the group Human Right Advocates in Negros (HRAN), has been a veteran of the labor and human rights movements in the island of Negros in the Visayas for years. But he said the attacks on civilian communities and activists have been unprecedented.

In Escalante, a city in northern Negros, the military deployed the Augusta Westland 109 helicopter in March 2022, firing rockets into the rolling hills of Barangay San Isidro. The hills, though not mountainous, are home to sugarcane fields, banana plantations, and rural farmers. The military claimed that there were no civilians in the area when the bombs fell. “They said it was a combat zone, but we know that people live there.”

One of the most severe incidents occurred in Himamaylan in 2022, where widespread military operations led to widespread evacuation of thousands.

That year, the Philippine Army’s 79th Infantry Battalion was roundly criticized by environmental groups for its plan to conduct an aerial strike on communities located at the Mandalagan Mountain Range in Negros Occidental. The said mountain range is part of Northern Negros Natural Park (NNNP), a key biodiverse area and a protected area in the Philippines. The Army also military operations in Barangay Minapasuk in May 2020.

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) declared NNNP as a protected area. It is the largest watershed and water source for seventeen municipalities and cities in Negros. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) also declared the area a Key Biodiverse Area.

Together with the Mt. Kanlaon Natural Park, the NNNP constitutes the largest portion of the remaining terrestrial forest ecosystem in Negros. It is home to many threatened, endangered, and endemic species, including the Visayan spotted deer, Red Lauan, Visayan warty pig, Negros bleeding-heart pidgeon, and the Negros shrew.

“They bombed areas near the Visayan hornbill habitat and large balete trees,” Gelle said. “These are places that should be protected.”

He also recounted how the military closed off access to the bombed areas, citing the presence of anti-personnel mines. "They told people they couldn't go back because of mines, but in reality, it’s likely that there’s unexploded ordnance from the bombs they dropped."

“The fear in the communities is overwhelming. Helicopters come, bombs drop, and lives are shattered. And yet, there’s no accountability. We don’t even have proper documentation of the damage these air strikes have caused,” he added.

In Negros, where land monopoly is still the norm and livelihood are already precarious, these aerial bombardments add another layer of devastation. “It’s not just the ground war that’s killing people here,” Gelle concluded. “It’s the war in the sky.”

Waterfalls located in Northern Negros National Park. (Wikimedia Commons)

Waterfalls located in Northern Negros National Park. (Wikimedia Commons)

Negros Bleeding Heart Pidgeon. (Dylan Mckenzie/Wikimedia Commons)

Negros Bleeding Heart Pidgeon. (Dylan Mckenzie/Wikimedia Commons)

Visayan Spotted Deer. (Wikimedia Commons)

Visayan Spotted Deer. (Wikimedia Commons)

Visayan Warty Pig. (Wikimedia Commons)

Visayan Warty Pig. (Wikimedia Commons)

“They said it was a combat zone, but we know that people live there.”

Felipe Gelle

Human Rights Advocates in Negros (HRAN)

Based on the data collected and analyzed by Altermidya, the military only hit actual rebel positions 17.4 percent of the time. Out of 173 cases of bombings, shelling and strafing, only 30 were confirmed New People's Army (NPA) units or camps. The military, though, includes some civilian communities as part of the rebel network and may consider them "legitimate targets."

Lumad children struggle with PTSD, depression

“When a community is bombed, all Lumad schools and communities are affected.”

Rose Hayahay, who began her work as a Lumad volunteer teacher in 2018, recounted how the military began intensifying its attacks on the communities with Lumad schools after martial law was declared in Mindanao in May 2017.

"When martial law was declared in Mindanao, no less than 75 percent of the regular Armed Forces of the Philippines were deployed there," she recalls. Outside the Marawi siege, communities of Lumad indigenous people of Mindanao were openly targeted in President Duterte’s declarations.

Twelve schools shut down in Davao de Oro, and the community subjected to aerial bombings from 2017 to 2022. After the bombings, displacement followed, forcing families to evacuate to Haran evecuation center in Davao City, where they continued to experience military harassment.

Mawing Pangadas, who was in Grade 7 when the bombings began, remembered how his community was thrown into chaos."

We were scared, and there were students hanging around our school while the military was shooting on the other side. It felt like there was no enemy,” he said.

Describing one particular bombing incident in 2017, he recalled how students were playing outside when a helicopter suddenly dropped bombs near their school. "We ran back into the school and hid because we were scared of the bomb's loud noise."

The trauma inflicted on the children was immense. "One hundred percent of the children, have PTSD and depression," said Teacher Rose. Mawing added that the attacks made students lose hope in education. "It seemed they lost hope of continuing their education," he added.

Teacher Rose, who accompanied Lumad students from one evacuation to another, recalled that in Manila during a New Year’s Eve celebration, the kids would recoil in horror at the sound of exploding firecrackers.

“It was Christmas time, of course there were fireworks in Manila. They all cried and cannot sleep,” she recounted. “Even the sound of doors banging would trigger them.”

These testimonies highlight not only the physical destruction caused by military operations but also the psychological toll it takes on the Lumad children.

Teacher Rose Hayahay recounts the experiences of indigenous Lumad children under aerial bombardment in Mindanao, in her testimony before the International People's Tribunal in May 2024.

Teacher Rose Hayahay recounts the experiences of indigenous Lumad children under aerial bombardment in Mindanao, in her testimony before the International People's Tribunal in May 2024.

Mawing Pangadas, right, with brother Ismael in 2022. They were detained by cops on trumped-up charges before being released in 2024.

Mawing Pangadas, right, with brother Ismael in 2022. They were detained by cops on trumped-up charges before being released in 2024.

At 9:52 in the video, President Rodrigo Duterte declared that he will order the Philippine Air Force to bomb the Lumad schools in Mindanao on July 24, 2017. Heavy aerial attacks against Lumad communities commenced. After the President's signing of Memorandum Order No. 32 in November 2018, heavy aerial attacks against supposed rebel positions also commenced across the country, particularly in Eastern Visayas, Bicol and Mindanao.

Friendly fire?

Altermidya found at least five (5) instances of "friendly fires": AFP aerial attacks inadvertently hitting their own ground forces. We validated these instances with reports from locals who witnessed the bombings, local human rights groups who monitored these events or local news reports:

Barangay Hinagonoyan, Catubig, Northern Samar: On December 16, 2017, residents witnessed the area being hit four (4) times, reportedly using a 105mm Howitzer. There was previously an encounter between 20th Infantry Battalion and NPA. According to residents, "6-9 government soldiers" were hit in a friendly fire.

Barangay Datu Wasay, Kalamansig, Sultan Kudarat: On February 5, 2019, AFP allegedly dropped bombs after an armed encounter with the NPA. At least 20 elements of Marine Batallion Landing Team-2 (MBLT-2) were reportedly killed in friendly fire, according to reports.

Sitio Maro, Barangay Senuda, Kitaotao, Bukidnon: On June 25, 2020, AFP shelled the area repeatedly near the position of troops from 3rd IB. At least two soldiers were said to be killed in the bombing. This was followed by rocket attacks and strafing in the area, leading to government troops fleeing the area.

Palimbang, Sultan Kudarat: On December 22-27, 2020, a series of bombings was done by AFP in the area against rebels. At least 21 AFP troops were reportedly killed in a friendly fire during the bombings, according to sources.

Barangay Bayombon and Biyong, Masbate City, Masbate: On August 23, 2021, two Black Hawk helicopters bombed the area three (3) times and strafed five (5) times. No rebels were killed, but nine (9) government troops were reportedly killed in friendly fire, while a military asset was injured.

Altermidya sought out the AFP Public Affairs Office for an interview or to comment on this story. As of this writing, they have not responded to our repeated requests and follow-ups.

Seeking accountability

The Philippine military claims that these military operations target communist insurgents. Yet Altermidya's findings show that only a fraction of these attacks successfully hit rebel targets, with the vast majority of victims being civilians. These attacks have resulted in the loss of lives, destruction of homes, and the displacement of entire communities, contributing to a climate of fear and violence in the countryside.

Civilian communities and human rights groups have repeatedly called for accountability, but the response from local authorities has been inadequate. This apparent lack of justice has driven civil society groups and victims to seek recourse in international bodies. The persistence of military violence, with little attention paid to the collateral damage suffered by civilians, has prompted human rights organizations to escalate their grievances to a court of "moral suasion," the International People's Tribunal. It convened on May 16-17, 2024 in Brussels, Belgium.

Testimonies from survivors, victims, and human rights defenders were heard in the IPT (both this year and the previous gathering, in 2018). The said tribunal found the Philippine government (both the Duterte and the Marcos administrations) guilty of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) violations. Among the tribunal organizers' first acts was the submission of their findings to the International Criminal Court (ICC), which is in the thick of its investigation on President Duterte and the conduct of his bloody war on drugs.

Whether this will lead to tangible changes in government policy or military conduct remains uncertain, but the collective efforts to bring these abuses to light have raised global awareness of the plight of vulnerable communities in the Philippines.

Negros-based farm worker Butch Lozande of the National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW), a witness during the 2018 hearing of IPT, was among those who joined the Philippine delegation of activists who filed complaints against Duterte before the ICC in September 2018. (KR Guda)

Negros-based farm worker Butch Lozande of the National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW), a witness during the 2018 hearing of IPT, was among those who joined the Philippine delegation of activists who filed complaints against Duterte before the ICC in September 2018. (KR Guda)

Filipino activists in May 2024 protest call on the ICC in The Hague, The Netherlands to act on their call to hold the Philippine government accountable for war crimes.

Filipino activists in May 2024 protest call on the ICC in The Hague, The Netherlands to act on their call to hold the Philippine government accountable for war crimes.

"We are reminding (government forces) that the bombing of schools, hospitals, or any civilian institution violates IHL (International Humanitarian Law). It is the responsibility of the State to respect this. Schools are zones of peace and are regarded under IHL as protected civilian objects. Attacks on schools during conflict is one of the six grave violations against children in situations of armed conflict identified and condemned by the UN Security Council."

Chito Gascon, Philippine Commission on Human Rights (CHR) Chairperson, August 11, 2017

This special report was made possible through a grant provided by the Asian Investigative Reporting (AIR) Network.